This movie is a fictionalized account of a real-life woman who was rumored to be the Grand Duchess Anastasia, the only one of the five children of Czar Nicholas II to have supposedly escaped death when the royal family was murdered during the Russian Revolution. Wandering about Europe under assumed names, this starving princess on the run lives a life in exile.

Anastasia, or Anna Anderson as she is also known, is not the only exile returning from self-imposed banishment. This movie marked the return to films of Helen Hayes, who had not made a movie in about 20 years, and had curtailed her theater and television performances somewhat in the aftermath of the deaths of her daughter from polio (mentioned in this previous post on polio depicted in films), and of her husband, writer Charles MacArthur.

But by far, the most conspicuous exile of the group is Ingrid Bergman. This film was considered her return to Hollywood after seven years in Europe when she caused a scandal by leaving her husband and daughter for her lover director Roberto Rossellini in Italy, and having a child out of wedlock by him. She was denounced from pulpits and in Congress, which may seem like something out of “The Scarlet Letter” today, but one must consider how famous, and how beloved a star Miss Bergman was in the United States in the 1940s. (Teenager Grace Kelly listed Bergman as her favorite actress.) In that conservative era, she was regarded as a betrayer of American morals.

In “Anastasia”, Ingrid plays the starving street person who opportunist Yul Brynner, a former general in the former czar’s former army, scoops up to feed, and nurse back to health, and train to impersonate the Czar’s daughter Anastasia, who miraculously escaped execution in Russia. There’s a fortune in the Bank of England for anyone who can prove to be the missing Romanov, and he wants some of it.

The plot, though based on the fact that there was such a woman who was rumored to be Anastasia, is fabricated. The characters played by Yul Brynner and his henchman did not exist. As we discussed in our two previous posts, fantasy and reality mix it up a bit in princess stories, and in this case, the truth loses.

The story is essentially not a documentary, but a romance, and not the kind between winsome princess and handsome commoner as in our two previously discussed films, “Roman Holiday” and “The Swan”, but a love for a country that has vanished, for the past that can never be reclaimed, and for life itself, which many Russian nobility discovered in exile after the Revolution. Both Yul Brynner and Ingrid Bergman have this passion for survival which makes them grasp at crumbs, hopes, and opportunities, and perhaps eventually, for each other.

Set in Paris, 1928, some ten years after the Romanov dynasty ended by abdication, and then execution, in Russia, this chaotic world is the aftermath of the staid world of Grace Kelly and Alec Guinness in “The Swan”, before World War I when middle European royalty were all pretty much related and maintaining the status quo was the object at hand, before the masses got ugly and demanded independence and revolution.

“Anastasia” has rather more in common with the post-World War II environment of Audrey Hepburn in “Roman Holiday”, when what monarchies remained after the conflagration were upheld by ancient families sometimes ill equipped to guide their nations into the modern era. At least Audrey Hepburn had a country. Ingrid Bergman, in “Anastasia” has lost hers for good.

This world is established for us pretty quickly when we see a cab driver, a former nobleman, in the community of Russian exiles in Paris, being addressed as “Excellency” and haggling over a fare. Yul Brynner runs a nightclub. Here, the nobility survives by learning how the other half lives, unless of course they managed to escape Russia with their fortunes intact, as in the case of the Dowager Empress, played by Helen Hayes.

The story is told partly with the romance of a fairy tale, and party with the skepticism of the modern age. On the one hand, we first see Ingrid Bergman attending the Russian Orthodox Church at the Orthodox Easter services, which plants a seed of her authenticity for us. But, Yul Brynner’s mercenary attitude toward her, coaching her in facts about her own life, and her obvious ignorance of many facts lead us to believe she is a fake. At other times, she knows things about Anastasia only Anastasia could know. We are never allowed to be certain about this woman. Later, Brynner will also become uncertain, and even Ingrid will not really know the truth. It will become a movie not about what she is, but what she wants to be.

Yul Brynner is fascinating in this movie, commanding, sexy, striding about with his military bearing, even when he bends to kiss a lady’s hand. When he does this, it is never with cloying obeisance, but as with the stiff drop of his head to indicate a bow to a gentleman, Brynner is a case for those who would show proper courtesy not to humble himself, but as a manner of maintaining his own prodigious dignity. It is beneath him not to display courtesy.

Like Gregory Peck in “Roman Holiday”, he is both part fairy godfather and part prince, though Anastasia will have another prince to deal with as well. Brynner also, like Peck, intends to exploit his princess, but Brynner is ten times more mercenary. He is ruthless, and knows much more about survival. He twists convention for his own means, and is more successful at this than either Gregory Peck and Louis Jourdan, perhaps because he is more ruthless.

Ingrid Bergman was about 40-ish when she made this film, playing a woman meant to be at least 10 years younger, but she conveys this well, especially since her character, while troubled and beaten, is not fey or innocent like our other princesses. Her maturity, even in her bone weariness or in her most tormented expressions, is beautiful. She is sensual, in part because of her knowledge of life, just as Brynner seems more virile in his passion for survival.

When she first grasps Brynner’s scheme to turn her into Her Imperial Highness, the Grand Duchess Anastasia, she breaks down in hysterical sobs the first time she says her name. Names, it seems, are very important to princesses. They usually have so many titles, that a single name of significance might be a treasure. Grace Kelly implores Louis Jourdan to call her by her first name, wants to hear him say it. Audrey Hepburn wants to be called her nickname, Anya, by Gregory Peck, to hide her real identity.

When Ingrid is prepped and ready for a test, Brynner puts her on display to gain the official endorsement of the Russian community in exile, a part of establishing her legitimacy to the inheritance. A few accept her, with tears, as their monarch, but not enough. So, Brynner rolls the dice and opts for a big risk, to take her to see the matriarch of the Romanov family, now living in exile in her castle in Copenhagen. This woman is the Dowager Empress Maria, who is Anastasia’s paternal grandmother, played by Helen Hayes.

Some filming was done in Copenhagen and this, like filming in Rome during “Roman Holiday” adds to the realism of the setting and the story, but curiously, with a toy soldier-like royal guard marching in the streets, it seems storybook-ish again.

Brynner has dressed Bergman mostly in high-necked blouses and long skirts, pre-war style, which makes her stand out as an anachronism among other ladies in their late 1920s fashions, but then she is meant to be an illusion.

The illusion will get to be more than either Brynner or Bergman can bear the closer they get to reaching their goal of Grandmother’s acceptance. Their relationship takes erratic turns. After a nightmare, Ingrid receives no comforting like Audrey Hepburn’s overwrought princess. Brynner orders her to bed, like a strict father. In order to gain admission to Grandmother Helen Hayes’ inner circle, Brynner works his charm on Prince Paul, the old lady’s nephew who is financially dependent on her. Brynner expects Ingrid to work her charm on him, too, and practically prostitutes her to get playboy Prince Paul’s interest.

When the Prince takes the bait as Ingrid performs a champagne-inspired tipsy femme fatale act (where she ruminates on the realities of Cinderella), Brynner suddenly loses his enthusiasm for this whole charade. We suspect, though he never confesses it, that he might be jealous.

Through their relationship, Ingrid has relied on him, and as she grows stronger physically and emotionally, she begins to challenge him and stand up to him, making him question not only who she really is, but how he really feels about her. After a fight between them, and she agrees with resignation to attempt to court the favor of Helen Hayes.

Through their relationship, Ingrid has relied on him, and as she grows stronger physically and emotionally, she begins to challenge him and stand up to him, making him question not only who she really is, but how he really feels about her. After a fight between them, and she agrees with resignation to attempt to court the favor of Helen Hayes. Brynner kisses her hand, as he has done with so many of his victims, but this time it is a real gesture of comfort and tribute to her as a lady and what she has been through, whether or not she is actually a Grand Duchess.

Martita Hunt pulls out all the stops playing the fluttery Baroness von Livenbaum, lady in waiting to Helen Hayes, and the gatekeeper to the old lady’s privacy. She gets some of the best lines and delivers them with aplomb.

“Russia!” she indulges in homesickness, “I am all of Chekhov’s three sisters rolled into one! I shall never get back there!”

When Brynner asks if her life here in exile with the Dowager Empress is happy, she retorts that with Helen Hayes, “Life is one eternal glass of milk!” (Shades of Audrey in “Roman Holiday” and her dreaded nightly glass of milk, “Everything we do is so wholesome.”)

Later, when difficulties arise the Baroness repeats her exile’s mantra, “Well, I survived the Revolution, I suppose I can survive this.”

She helps him set up a “chance encounter” with Prince Paul and the Dowager Empress at the Royal Theatre. The scenes filmed here are opulent and grand, and evocative of the life they must have known in Russia. Brynner, along with his white tie and tails, wears his now defunct Imperial Russian Army decorations. They are all playacting.

All but one.

“I have lost everything I have loved,” Miss Hayes declares, “my husband, my family, my position, my country. I have nothing but memories. I want to be left alone with them.” She refers to Bergman as an imposter, but sneaks a look at her through her opera glasses.

Helen Hayes decides at last to meet this woman calling herself Anastasia. It’s a great scene between her and Bergman, two serious actresses with a knack for playing off each other. Hayes was actually only about 55 or 56 when she made this film, only about 15 years older than Bergman, but she is as effective playing her grandmother as Ingrid is in playing younger.

Bergman seems more truly desperate to be believed than she did in earlier scenes when Brynner put her on public display for committees of exiles in Paris, and pleads with this woman she calls Grandmamma to accept her.

“We are most of us lonely,” Helen Hayes dismisses her, “and it is mostly of our own making.” It is a drawing room showdown, like in the “The Swan”, with verbal tactics because this film, like “The Swan” was derived from a stage play, and so what happens in confined places is far more intense than any obligatory outdoor scene.

Hayes’ transformation from skeptic to believer is skillfully arrived at and happens only by turns. Bergman’s piteous pleas for love, for acceptance, wears the old lady down. Grandmamma wants to remain resolute before this clever impostor, but the fear nags her, grows in her, that what if this is really Anastasia?

Miss Hayes finally embraces her and Ingrid sobs, hopeless and heartbreakingly as she did when she first said her own name, which is now official because Grandma says so.

“You’re safe, Anastasia,” Miss Hayes comforts her, herself in tears, “You’re with me, you’re home!” But then, the codicil to the inheritance of her heart, “But, oh, please, if it should not be you…don’t ever tell me.”

It is another reminder, a late-breaking bulletin that we are living in a more skeptical age.

But Prince Paul is only too happy to believe with no reservations, and he intends to marry her. Her inheritance will mean he can finally be independent of the old lady.

While Brynner, the man who pulled the rabbit out of the hat, is thoroughly sick of the whole business and just wants out. It’s like the old saying, “be careful what you wish for because you may get it.”

He is a bit jealous of her relationship with Prince Paul and angry at her, now that she is going to be presented to society and to the world as the Grand Duchess.

“They don’t care about you,” he barks, “They don’t care who is Anastasia so long as they can get some money and position in a world that is dead and buried, and should be!”

So far, he is the only exile from Imperial Russia who accepts the collapse of the Romanov Dynasty, and it seems to be his disgust over losing Ingrid that has convinced him he does not really want her to be Anastasia. Ingrid is having doubts of her own, now that she understands that even though she is certain of who she is, she will never be certain if she is loved for herself, or for her money and title.

When next we see her, she is dressed in her long formal white gown with her decorative sash, and a tiara to indicate she is royalty. She looks rather like Audrey Hepburn in the opening ball sequence of “Roman Holiday”, and we realize this is where we came in. The 1950s princess, an illusion of the romantic past, on the precipice of an uncertain future.

The comic lady in waiting Baroness von Livenbaum adds her own indictment to the post-war era, making an observation that travel, among other things, is not as elegant as it once was.

“They don’t know how to make baggage nowadays,” she gestures to her opulent formal gown, “Imagine trying to fit this into a nasty little modern suitcase. The times aren’t made for elegance.”

The 1950s American suburban princesses might agree. In the next decade, their long, wide skirts with petticoats, their tiaras will disappear for a sleeker, more modern look. In another generation, their daughters will abandon hats and gloves. Their granddaughters will dress, and speak, and act so casually that the line between casual and formal will be forever blurred, and the formal will largely become unknown and irrelevant. And, as Baroness von Livenbaum comically mourns, but could never predict, the luggage will diminish to a carry on plastic baggie.

As Helen Hayes advises Ingrid Bergman, “The world moves on…and we must move on with it or be left to molder with the past. I am the past. I like it. It’s sweet and familiar, and the present is cold and foreign. And the future? Fortunately, I don’t need to concern myself with that. But you do. It’s yours.”

What she is doing is saying goodbye, though Ingrid doesn’t realize it yet, and giving her permission not to be Anastasia anymore if she doesn’t want this. Here, we have the great twist on the princess stories. In our first two films, “Roman Holiday” and the “The Swan”, the two sad princesses give up their romances with commoners to attend to their duties to their families and their countries. But Ingrid has no country, and it’s easier to do whatever you want when no one else is affected.

She has the luxury to do what Audrey and Grace do not; so she takes the opportunity and makes like a princess: she runs away. We mentioned in the two past previous posts how running away seems to be a princess thing. We are meant to assume she has run off with Yul Brynner, and hang the inheritance and the title.

Helen Hayes, asked how she will explain this to everybody waiting in the ballroom below, in their uniforms, and flowing gowns and tiaras. Miss Hayes, the no-nonsense Dowager Empress Grandma, responds,

“Say? I will say, ‘the play is over. Go home.’” It is a fantastic ending line, and though I have not seen the stage play performed, I’ve always wondered if the actress “broke the fourth wall” and addressed the line directly to the audience.

The contrasting of reality and fantasy, after all, is part and parcel to examining the 1950s princess.

Reality, as well as a gesture to the romantic images of the past, plays a part in the real-life aftermath of the mystery of Anastasia. Many examinations were made of the woman known as Anna Anderson who claimed to be her, books written about her, and compelling arguments made pro and con for decades as to whether she was really Anastasia. She bore similar physical characteristics, her handwriting was supposedly very similar, but in a world without modern forensics, mystery and legend rule the day.

Grand Duchess Anastasia in her teens.

Until the day comes, of course, when modern forensic science steps in. This happened in the 1990s, when, after the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics crumbled into independent states including a reborn Russia, uncertain of its present or future, but seemingly more willing to deal with its past. The remains of the murdered Czar Nicholas II, his wife and three of his children were found in 1991, and through DNA testing something infinitely more useful but less romantic than the propagation of legend was revealed, that one of them was Anastasia. The woman known as Anna Anderson was indeed an imposter.

Two children were still missing, and their remains were found in 2007, 16 years later, in another location, and positively identified in 2008 as Anastasia’s sister Maria and her brother Alexei. It takes some stories a very long time to unravel and get to the ending. Their being separated from the other bodies may have been the genesis of the rumors of an escaping Romanov child, Anastasia or one of her siblings (there were various rumors), but we know with certainty now that none of the royal family escaped assassination.

Czar Nicholas II and his family. Anastasia is far left.

That is the efficient reality to the legend, but there occurred as well an official, even romantic gesture to the past. The first group of remains of the royal family were taken for reburial at the Cathedral of Saints Peter and Paul in St. Petersburg, where all the Russian emperors are buried, the new Russian government seemingly willing to bypass several decades of Communist condemnation of Russia’s imperial past.

Even the remains of the Dowager Empress, the Grandmamma, who died in 1928, the year chosen for the setting of the movie “Anastasia”, were exhumed in Denmark in 2006 and re-interned with her husband, Czar Alexander III in the Cathedral in St. Petersburg as well. This most resilient exile at last came home.

Ingrid Bergman, the exile in disgrace who made her reappearance in American film with this performance in “Anastasia” didn’t actually return to the U.S. quite yet. The film was made in Europe. She won her second Oscar for it, and her pal Cary Grant accepted it for her. It wasn’t until Miss Bergman appeared at the Academy Award ceremony in 1958 as a presenter that she made her first public return to Hollywood. She was given a standing ovation. All returning exiles should be so fortunate.

At the end of her life, Ingrid Bergman suffered from cancer (though bravely continued working), and died in August 1982, followed only a few weeks later by the death of Princess Grace. We are always saddened when we lose film favorites. For those who are too young to remember, that August and September was a bit of a shock for film buffs, and pretty tough for Cary Grant, who worked with and was close to both these actresses.

Princess Grace visits the idol of her teen years, Ingrid Bergman, during Miss Bergman's stage appearance in "Captain Brassbound's Conversion" 1971 or '72? Photo credit unknown at this time.

Both Bergman and Kelly were famous protégés of Alfred Hitchcock. The director had turned to Grace Kelly to be his new representative “cool blonde” when Bergman fled in her self-imposed exile from Hollywood. “Anastasia” was made the year Grace Kelly, in turn, fled Hollywood for life as a real princess, but Hitchcock evidently did not look back to Ingrid Bergman for inspiration. She was after all, in her early 40s now, and perhaps the great master of suspense found no sexiness in that.

We have a drastically different view of aging and sexiness today. I half expect to read in People magazine one of these days that 40 is the new 16.

All three actresses, Audrey Hepburn, Grace Kelly, and Ingrid Bergman, were iconic figures of their era, and played their melancholy princess roles with degrees of innocence lost, sadness swallowed, and futures faced with resolute purpose. How much of a prototype they represent for all the American suburban princesses watching them, and copying them in style whenever they could, is debatable.

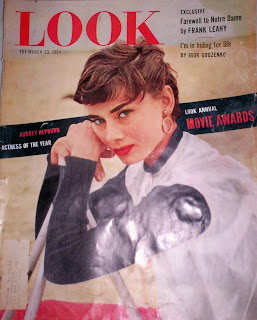

In the case of Audrey and Grace at least, their images leaped from just movie magazines onward to fashion magazines, women’s general interest magazines and Life and Look. As idolized as Hollywood stars have ever been, even since the silent film days, few have made that leap to mainstream icon, making any kind of Hollywood endorsement irrelevant.

The reality behind the illusion.

The ladies who would eventually trade tulle dresses with “skirts that whirl forever” as the New York Times ad referred to in Part 1 of this series put it, to simple sleeveless sheath dresses in the next decade perhaps also, like these movie princesses, found themselves facing unimaginable futures with resolute purpose. A generation later, their restless daughters would take their own futures and chances for happiness in their own hands, sans gloves, changing society a great deal in the process. Perhaps even a revolution.

We end this series on the 1950s princess with the interesting remark, applicable to these each of three film princesses, Ann, Alexandra, and Anastasia, made by one of Grace Kelly’s biographers, Robert Lacey, in Grace (G.P. Putnam’s Sons, NY, 1994) who surmised that one of the questions most wanted to be asked over the years by journalists of Princess Grace was,

“Are you happy?”