“3 Bad Men” (1925) is notable for the lovely union of 1920s filmmaking and present day film scoring. This John Ford directed silent Western was restored, with a new musical soundtrack added in 2007. The modern music composed by Dana Kaproff is extraordinarily evocative of American Western themes, and deeply moving in the way it re-interprets this old silent movie for a new audience.

(We recently discussed modern scoring of silents in the comments section of this post on “The Freshman” - see here.)

There are the traditional feathery piano chord plunking, standard for silent movies, to be sure, but this score soars with the use of guitar and fiddle. One particular musical theme which is repeated throughout the film is used to illustrate the feelings of the main character, Bull Stanley (played with great sensitivity by Tom Santchi.) He is one of the three bad men, and his loneliness, his sadness, and his redemption are all carried to us effortlessly through music.

The film takes us to the 1877 land rush. John Ford sets the scene with proclamations by President Ulysses S. Grant, shots of a three-masted bark carrying immigrants over the ocean to the new country. There are a few ethic slurs throughout this film, which Ford seems to attempt to balance out with a tribute to the diverse ethnic groups that come to settle the Midwest. This is not a pontificating film, however, in the style of perhaps D. W. Griffith. On the contrary, the film is actually very funny, with title cards that convey the same kind of dry wit Ford’s actors will speak in his later films.

We see American Indians also, and though they thankfully are not treated with the same kind of ethnic ribbing the newcomers get, still they are not fleshed out as human beings. They are used here seemingly only as symbols of a presumably dying culture, signposts to show us we are in the West, and the West is still wild but not for long.

Dan O’Malley, played by George O’Brien, is a devil-may-care Irish immigrant who encounters Miss Lee Carleton and her father, former Confederate Major Carleton crossing the prairie in their enormous Conestoga wagon, leading a small heard of thoroughbred racehorses. Miss Lee, played by Olive Borden is a lady by birth, even though the only time we ever see her out of trousers, boots, and cowboy hat is when she takes a bath. She is flashing-eyed beauty, independent, and sassy.

Bull, and his pardners Spade and Mike, played by J. Farrell MacDonald (who, like Santchi, played in over 300 films, last seen here in “My Darling Clementine” - 1946), are desperados, horse thieves, and overall ne’er do wells. But these old no-account saddle tramps have a lovable quality of humor that throws the audience for a loop and makes them reconsider what is “bad”. Bull, it will be slowly revealed throughout the film, has a sorrowful back story, wherein his beloved little sister ran off with a man who “promised” to marry her. Bull is looking for her, and for the man who took her away.

The man is Layne Hunter, a dishonest sheriff in a ramshackle gold mining town. He and his gang attack Lee and her father to steal their horses, just when Bull and his boys wanted to steal them. Bull and his boys counter-attack and chase off the horse thieves, but Lee’s father is killed. When Lee buries her face on Bull’s chest in tears, we see the beginning of a transformation for Bull, who is reminded of his failure to protect his younger sister. He and his boys, become Lee’s guardian angels for the rest of the film.

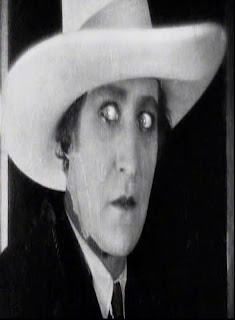

What is interesting is that Ford never makes these scenes too maudlin. There is a bit of overplaying here and there, as was the acting style in silents, but from the director’s point of view there is occasionally a startling cynicism to the film. The bad sheriff wears a white hat, and one senses this was Ford’s way of twisting our film Western iconic imagery. When Bull first comes up behind Lee, he thinks she is a man and intends to rob her at gunpoint, only lowering his gun in astonishment when she removes her hat and her hair falls to her shoulders. Dan O’Malley, who will eventually be Lee’s romantic interest, at first displays no interest in being her hero. In a muddy gold camp where cutthroats and dandies cross paths with prostitutes, only the new Protestant minister, whom an immigrant clothier with all due respect comically refers to as “Rabbi”, is all good, and the sheriff in the white hat, is all bad. Everybody else is drawn in shades of gray.

What is interesting is that Ford never makes these scenes too maudlin. There is a bit of overplaying here and there, as was the acting style in silents, but from the director’s point of view there is occasionally a startling cynicism to the film. The bad sheriff wears a white hat, and one senses this was Ford’s way of twisting our film Western iconic imagery. When Bull first comes up behind Lee, he thinks she is a man and intends to rob her at gunpoint, only lowering his gun in astonishment when she removes her hat and her hair falls to her shoulders. Dan O’Malley, who will eventually be Lee’s romantic interest, at first displays no interest in being her hero. In a muddy gold camp where cutthroats and dandies cross paths with prostitutes, only the new Protestant minister, whom an immigrant clothier with all due respect comically refers to as “Rabbi”, is all good, and the sheriff in the white hat, is all bad. Everybody else is drawn in shades of gray. There are impressive long shots of a massive expanse of prairie filled with wagon trains and cattle. The scenes of the land rush look so familiar, perhaps because they have been duplicated many times elsewhere. There are shots of charging wagons, toppling over each other, axels breaking, wagon wheels falling off, wagons charging right over the camera, and a shot of a man on a large-wheeled bicycle being towed by a horse. Many of these images you might also recognize in a similar land rush in “Far and Away” (1992) with Tom Cruise and Nicole Kidman.

There are impressive long shots of a massive expanse of prairie filled with wagon trains and cattle. The scenes of the land rush look so familiar, perhaps because they have been duplicated many times elsewhere. There are shots of charging wagons, toppling over each other, axels breaking, wagon wheels falling off, wagons charging right over the camera, and a shot of a man on a large-wheeled bicycle being towed by a horse. Many of these images you might also recognize in a similar land rush in “Far and Away” (1992) with Tom Cruise and Nicole Kidman.

Bull, Mike, and Spade drive Lee’s wagon and horses into the gold camp, and when Lee is approached by the flirtatious Sheriff Hunter, Bull gets protective and stands between them. The smarmy sheriff announces the unsavory reputations of Bull and his boys, unmasking them and hoping to shock Lee, who was ignorant that her protectors are desperadoes. What follows is another unusual scene, when Lee shows her tolerance as well as her moxie by cavalierly shrugging this off, “Come my three bad men, it’s time we were making camp.” She is a trooper, and when they agree to work for her for nothing, she asks with wonder, “Then you’ll be my men?”

They remove their hats with hesitant gallantry and nod, consenting to be owned. Seeing her holding another woman’s baby, Bull gets another pang of protectiveness, his slow guitar waltz plays, and we seem to see into his troubled soul.

Deciding she needs a better family than they, her men decide to go husband hunting for her. Spade and Mike, who are the more comic relief of the trio, tackle this, and their thirst, at the saloon, but Dan O’Malley eventually arrives in the gold camp, and resumes his attentions to Lee. He has Bull’s approval, because Bull has seen him punch his way out of the saloon. Therefore, he is a good man.

Conversely, we see here, and in other Ford Westerns, that women are depicted as the civilizing influence over the men and the bringers of civilization to the West. It is a romantic notion, but Ford, for all his macho movie fist-fighting, was really a romantic.

Bull is eventually reunited with his lost younger sister, Millie, who was shunted away by Sheriff Hunter among his prostitutes. Hunter’s gang tries to put down a revolt led by Bull against his abuse of power, and in the melee, Millie is shot. Their reunion is brief, and tragic. When Bull realizes that Sheriff Hunter was the man who led her astray, he punches through several doors trying to get to him.

Bull is eventually reunited with his lost younger sister, Millie, who was shunted away by Sheriff Hunter among his prostitutes. Hunter’s gang tries to put down a revolt led by Bull against his abuse of power, and in the melee, Millie is shot. Their reunion is brief, and tragic. When Bull realizes that Sheriff Hunter was the man who led her astray, he punches through several doors trying to get to him.When the minister, Bull, Mike, and Spade attend Millie’s grave the next morning, the wind whips their clothing, and it dawns on June 25, 1877, the day the land rush will begin at noon with the booming of Army cannon.

Life does not stand still, even for the grieving. Bull, Mike, and Spade, who have no personal interest in the land rush, continue to assist Lee and Dan to their promised land, and score revenge on Hunter, who is after them.

Each of the men, in separate acts of bravery, gives his life for the future of Lee and Dan, and so the three bad men are redeemed. In the final shot, a lump in your throat moment when we see their ghosts on horseback on the dim horizon are forever watching out for “our gal.”

The stunning action sequences are enhanced by a spirited fiddle reel, but the real soul of this film is so beautifully displayed in Bull’s theme of the slow guitar waltz. The classic Western is ironically made more classic with a modern touch. Despite Ford’s imprint and some laudable camera work, I can’t believe this film could have as much emotional impact without this lovely music.